November 20, 2019

By Amitai Bin-Nun, SAFE, and Kathryn Branson, PTIO

In mid-November, Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang published an op-ed depicting a grim future for American workers at the hands of automation. With the subtitle, “Self-driving trucks will be great for the GDP. They’ll be terrible for millions of truck drivers,” the op-ed painted technological advancement and the future of work as a zero-sum game.

While it is important to focus attention on the need to train, develop, and prepare the workforce for the jobs of the future, it is wrong to characterize technological progress as happening at the expense of workers. When it comes to innovation and the U.S. labor force, the choice does not have to be binary.

As organizations committed to maximizing the public benefits of autonomous vehicles (AVs), both PTIO and SAFE are dedicated to improving outcomes for the workforce of the future and wider society by embracing both the tremendous potential of automation and proactively preparing workers for the changes to come.

With the right policies and investments, the United States can enjoy the significant benefits automation provides while also supporting our workforce as we transition to an AV future.

So, what benefits can we already identify today?

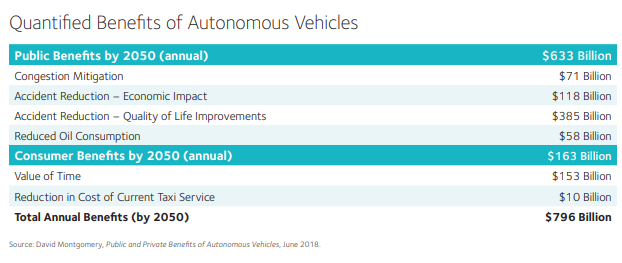

According to a SAFE report, America’s Workforce and the Self-Driving Future, publishedin 2018, full AV deployment could lead to nearly $800 billion in annual social and economic benefits by 2050.

(This table is a projection of the societal and consumer benefits of full AV deployment. These will phase in over time and cumulative benefits may exceed $6 trillion by 2050)

Cumulatively, these benefits will total as much as $6.3 trillion by 2050. AVs hold the promise of achieving such significant gains by greatly improving road safety—94 percent of fatal accidents are due either wholly or in part to human error—reducing congestion and vehicle pollution, and allowing people to reclaim time lost from sitting in traffic. Finally, the report makes clear that partial automation of trucks (up to Level 3) will not reduce employment, with additional studies projecting increases in trucking employment.

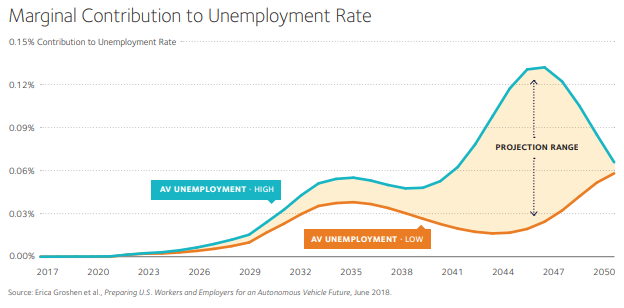

At the same time, our work continues in identifying, anticipating, and addressing the potential impacts AV deployment will have on the workforce. The SAFE study, based on work by scholars including Dr. Erica Groshen, the former commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Dr. Susan Helper, the former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Commerce, and Dr. J.P. MacDuffie of the Wharton School, found that millions of driving jobs could be partially automated over a time period of 30 years. In light of their analysis, we fully acknowledge that deployment of AVs could present challenges for some workers.

(This figure is a projection of the marginal increase in the unemployment range based on a more aggressive “high” faster deployment scenario and “low” scenario with slower deployment)

The good news is that since this transition will take place incrementally over an extended period of time, we have the opportunity to prepare and act proactively to ensure a smooth transition. We have, as a nation, done this before: Agricultural jobs went from 41 percent of American jobs in 1900 to 1.3 percent today—and in the words of MIT economist David Autor, “It’s not because Americans stopped eating.” Similarly, over the last 30 years, middle-class jobs have increasingly required computer skills, and the workforce has largely managed to keep pace with this evolving need.

How do we prepare the workforce for AV deployment?

First, we need to acknowledge the issue – both the opportunities and challenges. The attention it is receiving during the 2020 campaign is evidence of greater awareness of automation.

However, society would be poorer—by up to $800 billion per year by 2050—if we stifled innovation. Instead, we must engage in a broad range of policy efforts to 1) proactively work with stakeholders and technology developers to understand future skill needs and train drivers well in advance of any AV-induced displacement, with a particular concentration on jobs which overlap skills with drivers’ existing skill sets; 2) identify career pathways borne from deployment of AV technology; and 3) support evidence-based policies and programs to prepare workers for an AV future and mitigate any disruption.

Fortunately, some of these policy measures are already underway. SAFE and PTIO have endorsed the Workforce DATA Act sponsored by Senators Gary Peters and Todd Young, which would track and collect critical data measuring automation’s impact on the workforce that would support the policies discussed above.

Additional examples of the sort of policies that would support the workforce’s evolution with technology include those that foster a culture of lifelong learning, enabling workers to retool their skill set over the course of their career as their work needs evolve.

There are challenges in preparing the workforce for emerging technologies and there is no silver bullet that will solve this complex policy issue. SAFE and PTIO will continue to work for a broad range of thoughtful policies to answer outstanding questions around what AV technology will mean for the workforce through supporting additional research efforts, modernizing workforce training, and using evidence-based methodologies to ensure that society advances AV technology in ways that improve quality of life and economic opportunity for all Americans.